2023 Annual Newsletter

Jonathan Edwards Trust Newsletter: 90 Years of JE

December 2023

JE Dining Hall then and now. Photo credit 1: Unknown. Photo credit 2: Matias Guevara JE ’26.

Dear Jonathan Edwards Alums, Fellows, and Friends,

The Jonathan Edwards Trust is delighted to welcome readers to our second annual Trust Newsletter. By now, many of you are familiar with the Trust’s work in support of the JE community—funding programs and initiatives for JE students, fellows, and alumni that enhance the cultural, educational, and social life of the college. You can read more about the Trust and our mission on the Trust’s website or join the ongoing conversation on our Facebook page.

This edition of the newsletter features a conversation between JE alum, Professor Beverly Gage ’94, and JE’s former HOC, Penny Laurans, about Professor Gage’s Pulitzer Prize–winning book, G-Man; thoughts from the officers of the JE College Council; reflections by Paul North on the arts in JE and his first year as HOC; and, as the college celebrates its 90th birthday, notes on JE history from former JE Dean Mark Ryan, PhD ’74.

In addition, there’s a bit of Trust news to pass on. Predictably, it has been a busy year. Once again, the Trust has supported iconic JE programs for students like Culture Draw and the Fireside Chats for sophomores, helped to fund a portrait of former HOC Mark Saltzman, hosted reunion meet-ups and photo-ops for alums, refreshed the online JE store, hosted a successful JE tailgate at the 2023 Harvard-Yale Game, and more. And, as we look ahead, we have begun discussing a JE alumni and student event for 2025 with HOC Paul North.

The Trust has also seen some important changes during the past year. We are excited to welcome our newest trustee, Marco Davis ’92, President and CEO of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus Institute. You can read a bit about Marco here and here. Last May brought the retirement of long-serving trustee Gary Haller, whom many of you will remember fondly from his 12 years as JE’s HOC. Happily, Gary has agreed to become a trustee emeritus and thus, will not venture far. And finally, David Calleo ’55, PhD ’59, who served as a trustee for over 50 years, passed away in June. David had an enormously distinguished career as a political scientist; you can find a tribute to him here.

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the newsletter and wish you happy reading. If you would like to support the Trust’s work, you can donate here.

With all best wishes,

Eve Rice JE ’73

Chair, the Jonathan Edwards Trust

JE at 90: An Ongoing Community

Mark B. Ryan

Former JE Dean from 1976-1996

“This is a note that is long overdue.”

That was the subject heading of an email message I received a short while ago, written, it turns out, by someone who had graduated from JE some 45 years before. Now edging towards retirement after a highly distinguished career, Jonathan was reflecting on ways in which elements of residential college life had provided opportunities and challenges that “shaped me and changed the trajectory of my life in ways that I never could have imagined.” They had, he mused, “a greater impact than I realized at the time,” one that “has continued over the decades.”

On the grounds that its head was the first appointed and its fellowship the first gathered, JE can lay claim to being the oldest of Yale’s residential colleges, although seven of them simultaneously opened to students 90 years ago, in the fall of 1933. In that history, JE has a certain primacy: Robert Dudley French, the first and long-serving head, took a lead role in designing Yale’s college system, as it adapted the ideals, nomenclature, ethos, symbols, and physical structures of Oxbridge to a younger and more centralized American university.

JE under construction in 1931, and the newly completed courtyard in 1932. Photo credit: Unknown.

To his everlasting credit, HOC French instilled in JE a strong sense of community, among fellows as well as students. That tradition has continued ever since, with notably close ties among students, between students and administrators, and among fellows. Factions and dissention, no doubt, may have shown their faces from time to time, but clearly that sense of community prevails and has enlivened the impact that college life has had, over the decades, in helping to shape the trajectory of its denizens and associates.

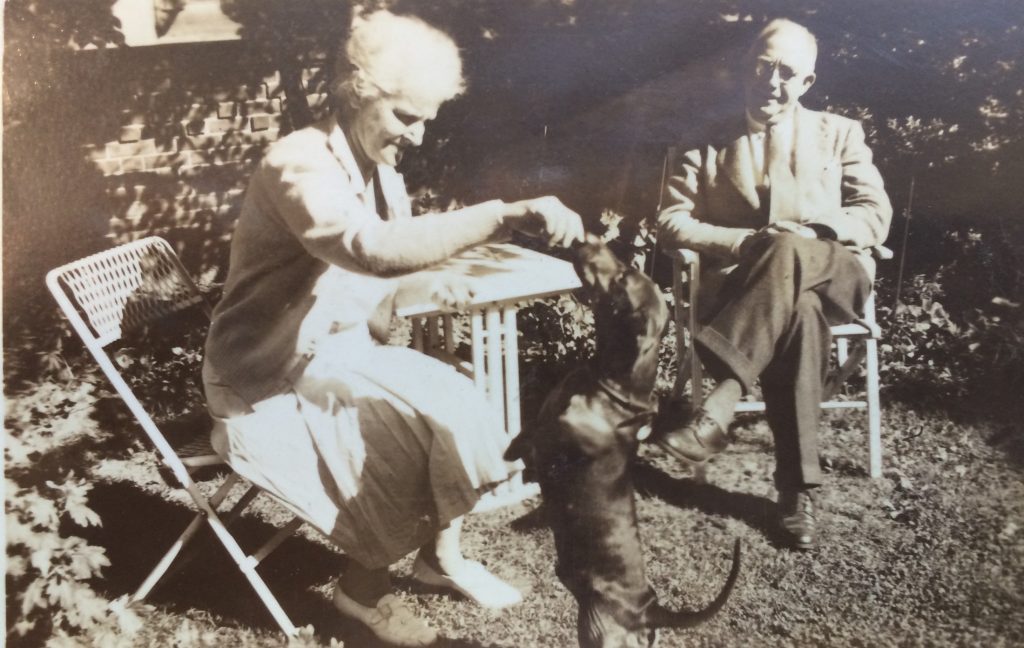

Head French with his family, circa 1945, and a portrait of Head French hanging in the dining hall today. Photo credit 1: Unknown. Photo credit 2: Matias Guevara JE ’26.

With no little astonishment, I realize that my own contact with JE, dating from 1976—as 20-year dean and subsequently as a fellow and member of the JE Trust—covers over half of its nine decades. Throughout that time, I have continually heard or read expressions of gratitude for the role that the college has played in students’ lives, often delivered, as above, after reflection from a decidedly later perspective.

Two collections of such expressions stand out in my own experience: in spontaneous remarks spoken privately at JE’s memorable all-class reunion of 2014, and in the submission of reminiscences included in The Spider’s Way, the history of JE published in 2020, which I had the nostalgic pleasure of editing. Both the reunion and the book brought together voices from JE’s full historical span, and they put in high relief the continuity of its communal spirit. A few other colleges held all-class reunions around the time of ours, but it seems no accident that JE’s drew by far the most participants, who clearly felt bonds among generations rooted in their memories of the college. Most moving to me were comments I heard from alumni about pivotal points in their Yale years and, as for Jonathan, about how support gained from some quarter in the college helped to resolve trying issues and/or set them on a fruitful path.

In The Spiders’ Way, contributors recalled with relish myriads of experiences that cemented their affection for the college. They wrote of physical spaces: the beauty of the neo-gothic architecture; the inviting intimacy of the courtyard; the magnificence of the dining hall; the views of the Art Gallery sculpture garden; the refuge provided by the Taft Library, the JE Courtyard, and facilities in the college basement.

The JE Common Room, then and now. Photo credit 1: Unknown. Photo credit 2: Kelly Tran JE ’27.

They wrote of receiving critical mentorship, advice, and support from heads, deans, and staff; of the powerful influence of teachers whom they knew, too, as resident fellows; of the inspiration gained from guests at college teas and from Tetelman Fellows; of enriching conversations with faculty fellows in the dining hall; of the value of discussions stemming from seminars and class section meetings held in the college; of the music that pervaded the college, year after year; of worlds opened to them through the Culture Draw and the printing press; of the terrors and rewards of presenting at the Paskus-Mellon Senior Seminar; of life-changing opportunities provided by the Bates Summer Traveling Fellowship.

They wrote of the high-spirited delight inspired by traditional social events such as the Toga Party, the Spider Ball, and Wet Monday; of the camaraderie and gusto felt on intramural sports teams; of the talents on display in recitals and dramatic productions in the dining hall, some of whose participants later gained fame as musicians, songwriters, orchestra conductors, and actors. The dining hall, one noted, was “our dream factory.”

Students in the JE Courtyard at a cookout in 1975 and at the start of the 2023 fall semester. Photo credit 1: Gary Collett JE ’78. Photo credit 2: Melissa Castaneda, JE parent.

They reflected on changes in the college since the days in which an all-male student body nightly wore coats and ties to dinner: on the adjustment—sometimes easy, sometimes not—to coeducation; on the ever-increasing diversity of student backgrounds; on their experiences during days of political turbulence and student activism.

There are moving character portraits of heads of college and their spouses; of administrators, fellows, and staff; and of students who later gained public prominence. Perhaps the most consistent theme recounted in The Spiders’ Way, I’d say, is friendship: the forming of bonds that have persisted ever since. Fellows write of ties formed in the Senior Common Room. Students recall the rich conversations, witty banter, and stirring debates of the dining hall; they write of insights gained from classmates, and of less erudite but bonding escapades. They mention crushes born in the dining hall, and a significant number tell of first meeting their future spouses somewhere in the college.

JE Revelers, circa 1973 and 2023. Photo credit 1: Margery Mark JE ’77. Photo credit 2: Matias Guevara JE ’26.

Bubbling up from those long and short rivers of memory, some spanning generations, are strong currents of love and gratitude—for the college and the people in it. Let one contributor to The Spiders’ Way speak for many, in a voice that resonates so well with that of my correspondent recalling experiences from 45-plus years ago: “Today, I look back through the veil of experience to my days at JE…,” he wrote. “I thank the universe for my time there.” And as a more recent graduate put it, “my experiences beyond the walls of the college continue to teach me that there is no expiration date for my membership in the JE community.”

No such expression, dear Jonathan, “is long overdue.”

If you would like information about obtaining a copy of the Spider’s way, click here.

Note from the JE HOC: Fall 2023

Dear JE Alums,

In my second year as head of college, I’ve started to focus on arts in and around the college, and I’d like to report to you a little on what’s happening. Students are mad for art, music, performance, and media work—they are snapping pics, singing, playing all the pianos in JE, planning theatrical productions from Brecht plays to Rent, and always, always wanting to mold materials into meaningful objects. Last year we had a marvelous exhibit in the courtyard by a young sculptor, Nathan Puletasi (JE ’24), who grew up between Samoa and Spokane, Washington.

Here is some of Nathan’s work on display in the courtyard last April.

Photo credit: Paul North.

Nathan’s small exhibit was comprised of materials and objects related to cowboy life: He literally took the guts out of the macho cowboy ethos he grew up around and displayed it in JE.

On another front, this year I inaugurated a new role in the college: JE artist-in-residence. Each year a promising artist will be on fellowship to work with students on their art projects and to advise them on exhibitions and on careers in the arts. Our inaugural JE arts fellow is David Jon Walker (MFA ’23), a brilliant type designer and graphic designer who is already creating a sensation, meeting with students and holding workshops. You can see David’s own work here.

Finally, I want to remind you of what you already know—JE is one of two colleges with a working letterpress print shop and the only college with a master printer, Jesse Marsolais, who possesses an encyclopedic knowledge of the art of printing. Jesse teaches an introductory course on printing each term and holds printing events where JE students get to know their letterpress. Recently the Yale News did a story on Jesse as a representative of the lively printing culture at Yale. You can see it here.

Photo credit: Yale News.

After jumping in as HOC last year, I definitely got more than my feet wet—I’m all in all the time now. And I take seriously the idea that residential colleges exist to educate “the whole person.” What can do that better than being around arts in process and in exhibition, and making things yourself?

I hope you hear in all these busy activities that students are fully recovered from the Covid interruption. Truly they are excited to be here; they’re in constant motion.

That’s the news from the beehive at this point.

Warmly,

Paul North

Head, Jonathan Edwards College

Note from current JE Students: JECC

Greetings all!

I’m thrilled to announce that, as the College approaches its ninetieth anniversary, your favorite volunteer, student-elected governing body, the Jonathan Edwards College Council (JECC), has filled its ranks with a new cohort of first-year representatives. On a Sunday this September, they joined sophomores, juniors, and seniors to convene the first full Council Meeting of the 2023–24 school year. Now made complete with our Farnam contingent, JECC is excited to invite revelry and nourish the heart of the community. Here’s a brief preview of our current endeavors:

- STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES

- Spider Cider: Free apple cider and Insomnia cookies are provided on Tuesday evenings in the Common Room for Spiders to take a break from studying and see friends.

- Big-Little Sibs: First-year students are encouraged to build bridges across grade levels upon automatically being assigned JE student mentors in their junior or senior years. We kicked off this year’s mentorship program with an ice cream social!

- JECC Food Nights: To ensure Spiders don’t go hungry, JECC sponsors monthly food nights that provide more sustenance than mere cider and cookies. Our first was a New Haven pizza tasting, which included pies from Pepe’s, Sally’s, Bar, Modern Apizza, and more.

- LANDMARK EVENTS

- Halloweek: As ever, we Spiders have an affinity for the spooky season! This year, JECC sponsored a pumpkin carving and a trick-or-treating event. Rumor has it that many older students in the college also continue to enjoy the *unsponsored* but storied tradition of liquor-treating.

- Picture Day: A new tradition in the making, this event shows that when we Spiders make the effort, we clean up nice. Photos are offered to all Spiders, including students, staff, and fellows in the college. No longer will our seniors have any excuse to use their high school prom photos as their profile pictures on Facebook.

- Johnny Ed’s Jolly Jamboree: Though the College has abandoned the term “Screw” to refer to its fall semester formal, there was little question that Spiders would find some excuse to celebrate the holiday season. This year’s formal, rebranded for us evolved young folk as Johnny Ed’s Jolly Jamboree– is scheduled for early December.

- (SOME) OTHER STUDENT NEWS

- JE Jobs: You’ve heard of a Buttery Manager, but have you ever met a JE Archivist!? In response to the phenomenal interest students expressed for working in JE, the College has hired archivists and photographers, filling out an all-star lineup of student workers in the College. Their work will surely be included in a future newsletter!

- Mental Health: JECC is working with Yale College Community Care, an office unveiled during the pandemic to support undergraduate mental health, and will spotlight our dedicated Community Wellness Specialist for the broader JE community.

![]()

JECC Spider Cider and Pumpkin Carving. Photo credit 1: Emmett Solomon JE ’23+1. Photo credit 2: Aqua Lake JE ’25.

As ever, we are grateful for the JE Trust’s and JE alumni’s engagement with and stewardship of the college! We appreciate your sponsorship of Culture Draw, and your patronage of our courtyard for your very long and definitely-not-distracting engagement photoshoots! If you find yourselves visiting the college on a Sunday between 11:30 a.m. and 12:30 p.m., stop by the Buttery and say hi! We tend to have extra food…

Very fondly,

Emmett Solomon JE ’23+1

Vice President, JECC

A Conversation between 2023 Pulitzer Prize Winner Beverly Gage JE ’94 and Former JE HOC Penny Laurans

Transcribed by Lydia Burleson JE ’21

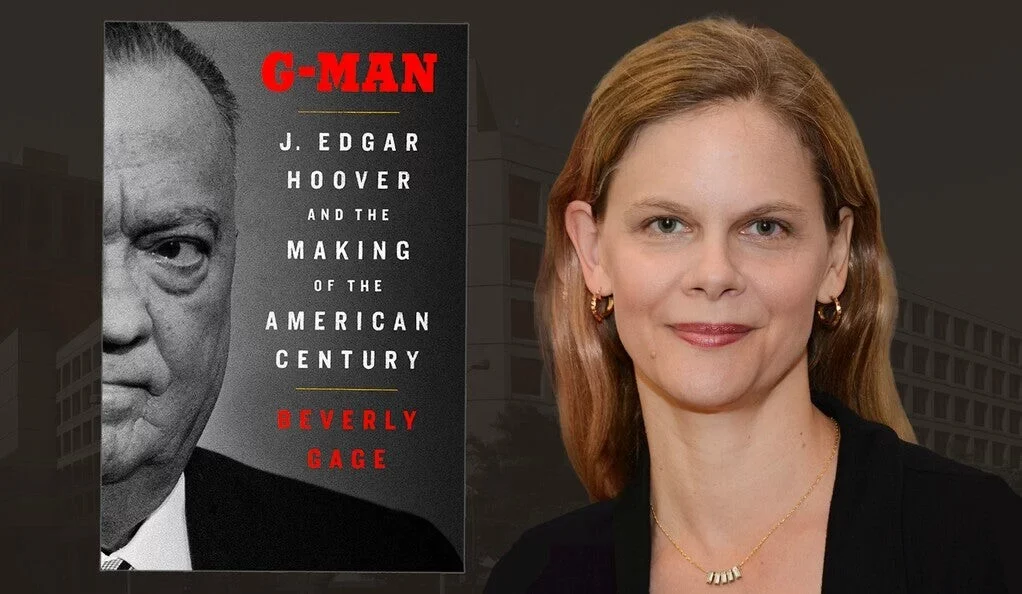

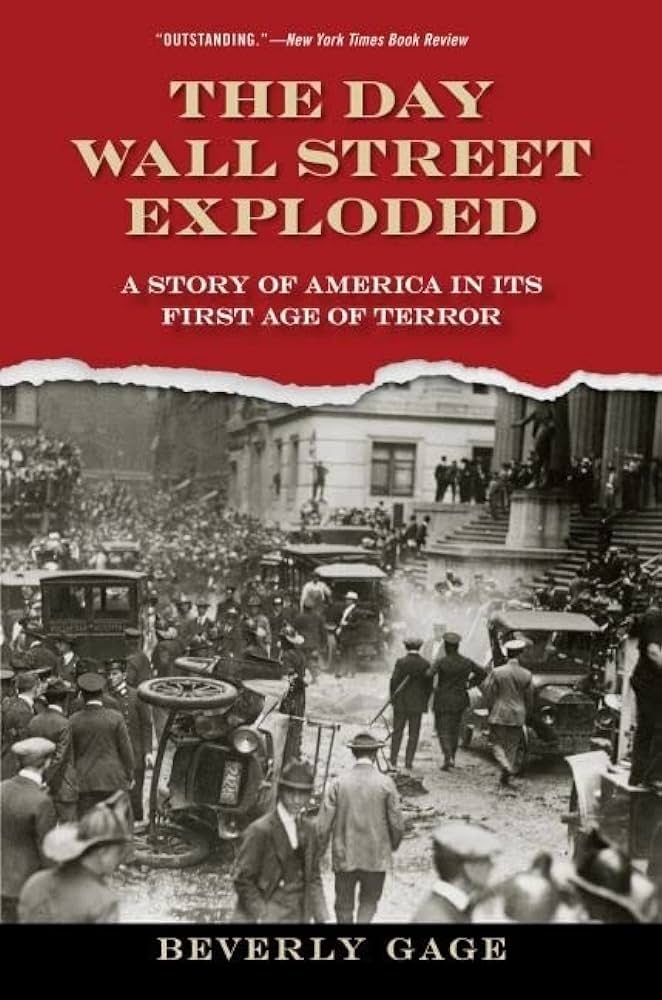

Recently, former JE head of college and current advisor to the university Penny Laurans sat down with Beverly Gage JE ’94, the John Lewis Gaddis Professor of History. The two discussed Professor Gage’s recent biography of J. Edgar Hoover, G-Man, which was the 2023 recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for biography, and Professor Gage’s journey from JE undergrad to widely celebrated American historian and professor of history at Yale. You may read their conversation below.

Professor Gage with her book G-Man. Photo credit: Yale News.

Professor Gage with her book G-Man. Photo credit: Yale News.

Penelope Laurans: Hey, Bev.

Beverly Gage: Hi.

PL: You’re the person of the moment. I hadn’t looked at all the awards you’ve won until recently. This is just insane: the New York Historical Society’s 2023 Barbara and David Zalaznick Book Prize in American History, the Organization of American Historians’ 2023 Ellis W. Hawley Prize, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in biography, the Pulitzer Prize. I could go on and on. This must give you a feeling of great satisfaction after all those years of work.

BG: It is a moment of satisfaction because, of course, as you’re working on a project this long, you wonder at many moments whether anyone will actually care and why you exactly chose to do this with the best years of your adult life. So it is really nice to have that all happen, and it’s nice to see that the world is still interested in and values 800-page books.

Beverly Gage accepts the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for Biography from Columbia University President Emeritus Lee Bollinger. Photo credit: Diane Bondareff/The Pulitzer Prizes.

The JE-Yale Years

PL: We’ll get into more of the book later, but I think we should start a little bit before that so that people understand something about you, and how you got to Yale and JE, and all of that part which you probably aren’t asked as much about when you go for all of these interviews with people.

I’ll start with a little anecdote. I was rummaging through the drawers in the JE press after I became head of college, and I uncovered this little card. It was beautifully printed, and it said, “Beverly Gage piano recital,” and I was overwhelmed by finding it, so I framed it and gave it to you. I thought that might be a good way to start asking you about how you got to Yale, and what you thought you were going to do, and maybe after that, a little bit about your life in JE.

BG: That card, that invitation to the recital is on my shelf in my Yale office. Occasionally students look at it and do a double take and wonder who this other person was. I came to JE in 1990. I came as a classical musician, and at the time, JE actually had this special program—

PL: Music in a Residential College?

BG: Exactly.

PL: And I taught Poetry in a Residential College.

BG: Yeah, I think these don’t exist anymore. Right?

PL: No, they don’t. And I can tell you why. Other heads of college became very jealous because first-year students were actually living in the college participating in these programs, which meant that all of the best musicians and all of the best poets were in JE, and this dramatically upset the other heads of college.

BG: As a student interested in those things, it was a great thing at the time, and it made JE really special and different from other colleges. During that first year, I was still a pianist—I had also been a violinist in high school but had sort of stopped doing that when I came to college. I was also interested in conducting and singing, and lots of other aspects of music, and so it was really fun and invigorating to be in this kind of intensive scene in JE.

PL: Was Leon Plantinga (the Henry L & Lucy G Moses Professor of Music, Emeritus) running that program at the time?

BG: He was.

PL: Leon, as everybody in JE should know, is the senior fellow in JE. He’s the person who’s been a fellow in JE the longest of anyone—the great musical historian, the author of wonderful biographies, academic biographies of Beethoven, Schumann and Clementi, and the leader of that program for a long time.

Did JE, did Yale attract you because of the music?

BG: It did. When I came to Yale, I was pretty sure that I didn’t want to be a professional musician, and so I didn’t want to go to a conservatory, which is one path. I really wanted to be at a school that was going to give me a broad education. But I did want to be someplace where you could do music at a pretty high level, and in the 90s anyway, Yale was the place that was known as the arts and humanities Ivy, and so I was really drawn to it for that reason; I think it still has a little bit of that reputation.

PL: Oh, no, Bev, it has a tremendous amount of that. In fact, I would say even the best. Many of the very strongest STEM students we get choose Yale over places like MIT or even Harvard or Stanford because they can also do music here, and I’ll just mention here Alex Nam, who’s not in JE—alas! he’s in Pauli Murray—but he just won the concerto competition. A phenomenal pianist. He is a math and philosophy major, I think. What you were attracted to still definitely exists in the reputation of Yale, definitely so.

BG: Of that cohort in the music program, maybe a dozen of us, about half went into something related to music, and the other half are off doing all sorts of other things. One member of that cohort became a Broadway composer and conductor, another is a violinist, I think, in the Boston Symphony. And another is the programming director, or some title equivalent to that, in Carnegie Hall.

PL: Wow! That is impressive. And I would say you could still find that and maybe it’s not concentrated in JE as it once was, but it’s definitely at Yale.

So, you come to Yale. Where did you go to high school?

BG: I grew up outside of Philadelphia. So I went to a high school called Strath Haven High School, which was the public high school in my suburban area. I grew up in a town called Wallingford.

PL: That’s good. Now, we’ve got you at Yale, and we know a little bit about your cohort. I think you also became close to at least one other person who became a historian. Am I right?

BG: My year at Yale, 1994, has produced this amazing number of prize-winning historians. There was Thomas Andrews, a Bancroft Prize winner; Imani Perry, who just won the National Book Award; and my own partner, John Witt, who’s a professor at the Law School. But it’s an amazing cohort, these folks who came out of it—Dave Leonhadrt, who is a New York Times columnist and writer just published his first book, which is very historically oriented. I could go on and on and on.

PL: Are all those people you mentioned in JE?

BG: No, John was not in JE. I don’t think Imani was in JE. But Dave Leonhardt was in JE.

PL: Tell us more. Did you major in history?

BG: I majored in American Studies.

PL: And who were your big mentors?

BG: I did a lot of my senior essay work and took a bunch of seminars with Robert Stepto, who was in American Studies and African American Studies. He was my senior essay advisor. And then because it was Yale in the nineties, I worked with a lot of junior professors who aren’t here now.

PL: Who? Are you still close to them?

BG: One was Bruce Shapiro, who used to do an investigative journalism course, who still lives in New Haven. He was actually my introduction to journalism. By the time I graduated, that is what I thought I was going to be doing, by way of Bruce and a few others.

PL: You wanted to be a journalist. That’s interesting, and maybe not surprising, because not everybody decides immediately that they’re going to go on for a PhD in history, especially in the nineties, or even now.

Tell us a little more about your trajectory after that.

BG: Well, as much as I was just singing the praises of the music program at Yale, I basically got to Yale and immediately quit all of the music stuff that I’d been doing. I spent my freshman year doing a lot of that–that recital that you found in the archive there was kind of my last hurrah as a real musician, and then I quit taking piano lessons. I did keep doing a little choral stuff and conducting but began moving away from music pretty quickly at Yale. I got interested in American Studies, particularly the field of history in American Studies.

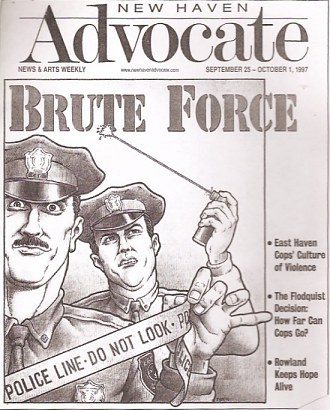

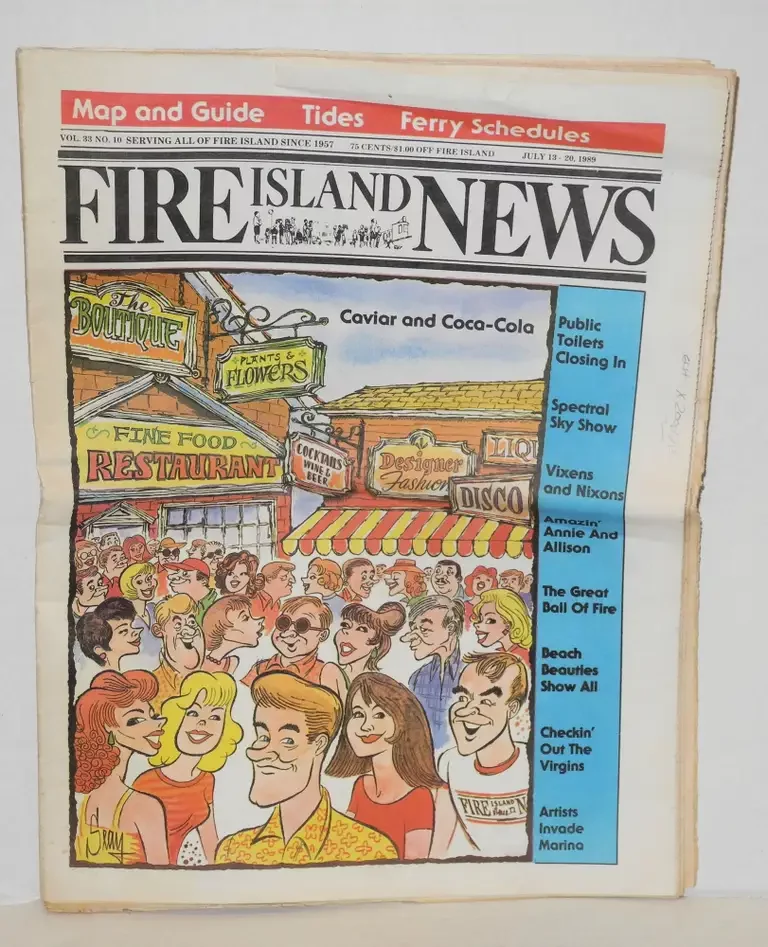

Then, in my senior year, I took Bruce Shapiro’s investigative journalism class and started interning at the New Haven Advocate, which was the alternative weekly paper that used to exist here. I never wrote for campus publications, but when I got involved in journalism it just seemed like a fascinating way to connect what I had been learning in the classroom with what was going on in the world around me. I was getting interested in politics and organizing, and it was a good way to do that, so I did that in one capacity or another, for three years after I graduated.

PL: And where did you do that, not at the Advocate?

Copies of The New Haven Advocate (1997) and Fire Island News (1989). Photo Credit 1. Photo Credit 2.

BG: Well, I did come back and work at the Advocate eventually. My first job out of college was at the Fire Island News, which meant that I went and lived on Fire Island, this little vacation island off the coast of Long Island, a kind of legendary place for New Yorkers to go. I spent my summer living out there reporting on basically three things. One was beach erosion. One was arrests for drunk and disorderly conduct. And then the other was all night gay beach parties because the whole east end of Fire Island has these legendary gay communities. That was my summer after I graduated. That was my first real job in journalism. Then I interned at the Nation magazine in the fall. And then I did come back to New Haven to work at the New Haven Advocate for a couple of years before—

PL: I love the Advocate. Did you know that the Advocate was originally owned by Dorothy Robinson’s (Yale’s Vice President and General Counsel for many years, now retired) brother?

BG: Geoff! Yeah, I knew Geoff well. I worked there when he owned it.

PL: It was very interesting because she was general counsel, and here her brother was running this—

BG: The muckraker, right? I spent a lot of those years critiquing and picking away at Yale, reporting on protest movements.

Graduate School at Columbia

PL: That’s perfect! When did you decide you wanted to go to graduate school?

BG: I started graduate school in 1997. In the fall of 1996, a couple of years out from when I graduated from Yale, I didn’t think that I was going to go back to graduate school, but after a few years of doing journalism, I realized that I liked books. And I really wanted some more time to read and understand the world around me. I ended up at Columbia for my studies.

PL: When you got to Columbia, how did you decide what you were going to do? I’m going to get to your first book in a moment, but maybe think of it that way. What was your trajectory like at Columbia? And as you move towards your first book, how did you decide what you were going to work on? Was that part of your dissertation?

BG: My first book was based on my dissertation. When I got to Columbia, I thought that I was going to study the history of prisons and incarceration. That was something that I’d been reporting about a lot at the Advocate and elsewhere. Prison populations were growing pretty dramatically in the late eighties and nineties, and so I thought that my interests were going to take me in that direction. And I did study some of that and think about it. And I’m not too far off from that, even at the moment.

But when I was in graduate school, I was doing some very basic reading in a textbook. I saw a mention of this event called the Wall Street Bombing in 1920. What initially drew me to it was that I had never heard of it, and that of all the studying I had been doing over the years, I didn’t have any way to understand how this big thing had happened. This was a bombing on Wall Street that killed almost 40 people, injured hundreds of people, shut down the financial markets—I mean, it was a big dramatic event in its day, and the thing that initially sparked my interest was that it had so thoroughly disappeared from our memory.

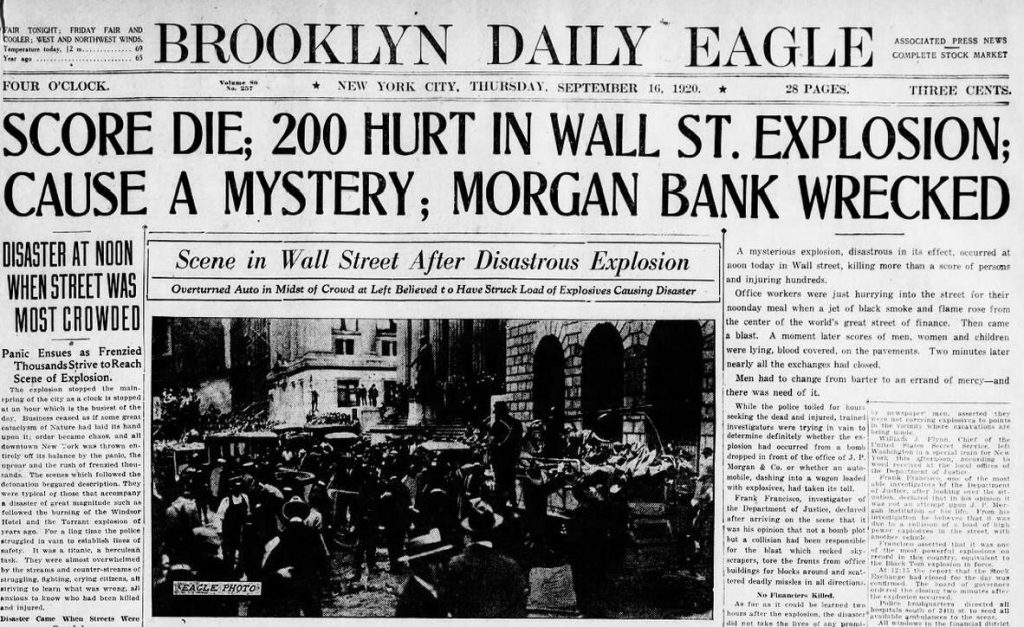

Headline from 1920 Wall Street explosion and the book that published out of Beverly Gage’s graduate dissertation on the topic. Photo credit 1. Photo credit 2.

PL: And did you discover that close to the time you were writing your dissertation?

BG: I did. I actually wrote a paper about it in my first year of graduate school, and then that subject kind of stuck with me, and so I decided to expand on that. My dissertation ended up being really about the bombing, the investigation into the bombing, the Red Scare politics that were around that, and then also going into a longer story about the politics of radical terrorism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. It was a lot of anti-capitalist violence.

I was actually already working on that and living in New York when 9/11 happened; I was living right across the river in Brooklyn and watched the towers fall from my rooftop, and experienced all that as a New Yorker. And for me, it had this extra layer because that’s what I had been studying. I’d been studying terrorism in the financial district, and so there were a lot of points of intersection, some points of rupture, too.

Professor at Yale

PL: Yes. Well, I want to get from that to biography in a minute. But tell us how you got to Yale again, because that’s a great job after graduate school. Did you come straight from Columbia? A PhD, then back to Yale as an assistant professor?

BG: I did. Even 20, 30 years ago, I had an entirely implausible experience on the academic job market, which is to say, I went on the market my last year of graduate school. I had just had a baby, and so I had this idea that, “this will take a few years. I’ve got the baby. I’ll wrap things up. We’ll take it nice and slow.” And I gave my first job talk ever, and it was at Yale, and they hired me, so I thought, “one says yes when opportunity knocks.”

PL: That is a one in a million experience in the nineties.

BG: 2004 was when I came here.

PL: Wow! Now was Joanne already here, Joanne Freeman?

BG: She was.

PL: You two were quite a pair in a way, because you’re both American historians. You focus on very different areas. You were both young and very, very up-and-coming and very able. But I don’t know that anyone could have predicted that you would be the smashing successes that you are. I like that because it means that smart people are looking at younger people and making good decisions and having faith in them. Do you feel that that was true in your hiring, that people had faith that you would grow and become maybe not quite what you are, but grow into tenurable people?

BG: I do think that Yale has made some really good judgments over the years, the history department. One of the pleasures of finishing this book, winning all these awards is I do feel that I’m paying back a bit of debt to the history department and the university, which supported me initially, when I did not have much of a track record, and gave me the time and the space and the support to do a project like this, which was long and laborious. They had faith that it would pay off.

Writing G-Man

PL: Well, of course, Yale takes tremendous pride in you, but it’s nice that you feel that you were supported along the way. The most important things at Yale are the students and the faculty. I’ve just finished writing a piece on Kingman Brewster that I’m going to circulate this weekend, and I will tell you the best thing about Brewster is that he had the opportunity to hire a great cohort of faculty, and even though he spent way too much money doing it, he improved the university in so many ways. It makes us so proud, if I can just speak for the university as a whole, to have people like you who have triumphed as you have.

Now we have to get into the Hoover book. Being able to do biography is a little different from being able to do other things. Did you have an inherent interest in biography? Or was it the subject matter that appealed to you, and you got into the complexities of doing a biography later? How did that go?

BG: I like the genre of biography in general, but I don’t think of myself as a biographer. I think of myself as a historian.

Hoover was a particularly appealing biographical subject, because he was doing such interesting things for his entire life, and his life really seemed to embody so many of the themes and trends in twentieth-century history that I was interested in. I was drawn to Hoover in particular, as a biographical subject, in a way that I don’t think that I would be drawn to a lot of biographical subjects, and that was because of his power, because his story as a person was also a big story about Washington, about social movements and high politics and the growth of the federal government.

J. Edgar Hoover, Director of FBI in his office, April 1940. Photo credit: Library of Congress.

PL: That’s interesting, because I would say this is a serious psychological study of an extraordinarily complex man. I’ve read all 800 pages. Unfortunately, I would begin quite late at night, and I would say, “Just a little more, a little more,” because I was gripped the whole way.

I think the most interesting thing for me was that I had one very superficial idea about Hoover, which was that he was this anti-communist, dark-side person who had tremendous power because of what he knew! Information is power, and he controlled a tremendous amount of information, and he held it over people. This was my view of him, which I think in the end probably wasn’t wrong, but it was way too unitary. I had no idea, absolutely none, that this was a man who was an amazing bureaucrat, who had enormous administrative capabilities. That part of him was utterly unknown to me.

Can you say something about that part?

BG: I’m happy to hear that you got out of this book exactly what I’d hoped people would get out of it. Which is to say that we have had a pretty one-dimensional view of Hoover very much like the one you described: the back-room actor pulling the strings, watching everyone, intimidating everyone, having the goods on everyone, and there’s certainly some truth to that. But I think the sources of his power were so much more varied than that, a lot of them having to do with his skills as a bureaucrat, as a political operator, and also as someone who knew how to make both himself and the FBI into these enormously popular household names.

For many people, one of the most surprising things in the book was just how popular he was during most of his career. That began to change in the 1960s, and he was a little less popular by the time that he died. But for most of the 48 years that he was at the FBI, he was not only powerful but pretty well regarded both in Washington and in the public at large.

PL: Yes, I think maybe my view of him was more slanted, because when I became aware of him, it was in the seventies, of course. And I knew about not just the racism but also what he had done to Martin Luther King, Jr. I think I have known for a long time that his operatives were recording King, and that even though I know he acted against McCarthy, he still had views that were very anti-communist.

One thing it might be interesting for other people to know is a little bit more about his relationship with the Kennedys. There are all these books about how he really was aware of the plot to kill President Kennedy. Is that credible?

BG: Hoover was head of the FBI under eight different Presidents, from 1924 to 1972, from Calvin Coolidge to Richard Nixon. Of all of those presidents, the period of the Kennedy administration was among the most dramatic in part because they really didn’t like Hoover, and Hoover really didn’t like them. And when I say them, I’m talking about John Kennedy in the White House, but also Bobby Kennedy, who was Attorney General and therefore was Hoover’s boss.

PL: He knew a lot about them, right? And a lot of it wasn’t good.

BG: He did know a lot about the Kennedys. He had actually been pretty friendly with their father. I think there are a lot of ways to explain what went wrong between Hoover and the Kennedys, some of which had to do with age, some of which had to do with general outlook. Hoover thought that Bobby Kennedy, in particular, was a kind of irresponsible, unqualified young whippersnapper—the president had appointed his 35-year-old brother as Attorney General. Hoover was not thrilled about that.

And then they had a number of internal clashes that produced very quickly real rifts between the two of them. Hoover knew a tremendous amount about John Kennedy’s sex life. There was a lot to know about Kennedy’s sex life. So there’s the moment in which, kind of famously, Hoover realizes that Kennedy is having an affair with a woman who was also having an affair with an important figure in the Chicago mob. There was that kind of stuff.

They got in conflict over civil rights enforcement, although the Kennedys were not nearly the civil rights heroes they’re credited for being today. In fact, it is Robert Kennedy who signs the wiretap orders allowing the FBI to wiretap King in 1963.

There are a lot of strange things about the Kennedy assassination, and there are a lot of strange things about Lee Harvey Oswald in particular, who was just a wild character. I did not do deep research on the Kennedy assassination, because that would have taken a lifetime in and of itself. That said, I am not much of a conspiracy theorist about the Kennedy assassination. I think there are some unanswered questions. I think there are some things that were done better and worse in the investigation, but I certainly do not think that the FBI conspired to kill John Kennedy.

Beverly Gage at work. Design credit: Zoe van Dijk.

What Next?

PL: I don’t want to over focus on the assassination because the book is very broad, and we can’t even begin to go into its full scope. I mean, just to entice people to read it, if they haven’t—learning about Hoover’s early life is fascinating. Learning about his partner and his homosexuality, even though he was virulently acting against it, learning about the way he manipulated power and stayed in power for eight consecutive presidents, learning about how this meshes with our national life, is utterly fascinating. If people haven’t read this book, it is like reading a biography, a mystery story, a story about our national life all in one. Read it!

But before we stop, I want to ask you what everybody I know is asking: after you’ve finished an 800-page book and are probably trying to have a little space and time, what next?

BG: Well, apparently I have to go back to teaching in January.

PL: What are you going to teach?

BG: I’m teaching my lecture course called The American Century, which is a big overview of the twentieth century.

PL: Oh, that is going to be crammed! Where are you going to teach it?

BG: I don’t have a room assignment yet, but they are all about to start registering for class. I have started over the last five or six years to get the children of many people that I went to college with in my classes.

PL: I get the grandchildren. I absolutely get the grandchildren now, so you have that to look forward to.

BG: If I’m lucky right? But I think when you finish a big project like the Hoover project, there are 2 impulses. One is–huh!—to take a breather. And many people have said, “Oh, this is great. You never have to write anything again.” On the other hand, when you work on something for so long, it means that you have this big backlog of ideas and other things that you’ve been wanting to write and haven’t had a chance to.

So I have plunged into two new projects. One is what I’m calling a road trip through United States history, where I’ve been traveling the country going to historic sites and thinking about the question of American national identity and how we express it or find it, or don’t, through our history. We’re coming up on 2026, which is going to be the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. It’s going to have a lot of pageantry attached. So that is a smallish book that I’m hoping to get out in the next year or two, before 2026.

And then my next big project: though I just said that I am a historian and not a biographer, I am going to write one more biography in my life, and that is going to be Ronald Reagan’s. So I’m just getting started on that. I do think of it as a little bit of a sequel to Hoover, because the question of communism and anti-communism as a structuring force of twentieth-century politics is the thing that makes the twentieth century go and make sense in lots of ways. Hoover only got me up to the 1970s on that, but Ronald Reagan’s going to get me to the end of the Cold War.

PL: Well, I wouldn’t even discuss national politics after Ronald Reagan, because who knows what they’re going to be, right? He’s certainly the kind of fascinating figure that allows you large scope. I think the project you discussed before that sounds equally fascinating.

So, this is wonderful. We’re incredibly proud of you at JE and glad that you still feel loyal to the college.

BG: That’s right. I’m still around JE, sometimes. And I’m grateful to JE for getting me started down this path.

PL: Well, I don’t know that JE got you started, but you were a part of a very able cohort of JE people in the nineties. I think it’s very wonderful to know that years later, not just JE people but Yalies are making significant contributions to literature, to history, to the national life. If we aren’t doing that, then we’re not properly educating people. You’re part of something that I think is incredibly important to Yale, and we’re very grateful for it.

Thank you for taking the time. You’ve been interviewed by so many famous people that I feel honored just to do this, and I know JE will feel honored to have you in its newsletter.

Thank you very much. Bev.

BG: Thanks for doing this, Penny.

If you’d like to engage more with Professor Gage’s G-Man, we invite you to listen to this Yale Alumni Academy lecture, available here. You can purchase a copy of G-Man from the Yale Bookstore here.

Student Spotlight: Rakel Tanibajeva JE ’24.5

Interview and transcription by Lydia Burleson JE ’21.

In addition to its rich alumni community, JE’s current students are taking steps to have an impact in the world. Rakel Tanibajeva is a current student entrepreneur working to bring more environmentally conscious solutions to the fashion industry and production world. Read a spotlight on Rakel below.

Rakel Tanibajeva at a Tsai CITY event. Photo credit: Rakel Tanibajeva JE ’24.5.

Year in JE: 2024.5

Where are you based when not in JE / at Yale? New York City

Describe your company (companies!) to us.

Lots of Berries

Lots of Berries (LOB) is an environmental design company based in New York that tackles fashion waste by producing custom-made, hand-designed high-fashion clothing made entirely from high-quality upcycled fabrics, and biodegradable fashion accessories made out of mycelium (the root fibers of mushrooms). LOB specializes in designing and producing unique, upcycled pieces that help my clients look, feel, and do good—for the environment, themselves, and others.

YouBio

YouBio is a sustainable production company manufacturing negative-waste, home-compostable protective packaging (and other products) out of fungi biomaterial. We are an entirely US-based, women- and minority-owned company, and our core values are innovation, quality, reliability, and affordability, as well as a commitment to making an environmental and social impact.

How did you become involved in environmental entrepreneurship?

After modeling professionally from a young age, I re-entered the industry as Sustainability Ambassador during New York Fashion Week 2020 and as the 2021 Refashion Week People’s Choice Award–winning stylist. I have collaborated with numerous environmentally conscious organizations, including Housing Works and Goodwill. In addition, my 2021 Urban Green Proposal to the New Haven Parking Authority was published in the New Haven Independent.

But the inspiration to become an entrepreneur in general stems from my unwavering passion for the wellbeing of the environment and the people inhabiting it, as well as my frustration with the lack of impact I was making through my past professional endeavors. By taking charge of my own venture, I can shape the business in accordance with my values, not only to make a profit but to also to make a tangible and positive impact on the world and people in it for current and future generations.

YouBio business card and fungi shipping products. Photo credit: Rakel Tanibajeva JE ’24.5.

How have you managed Lots of Berries and YouBio while also being a student?

Simply put, being a student founder is not easy, and prioritization, time management, and sacrifice are necessities. There are only so many hours in a day, and over the years of my entrepreneurship I’ve become better at balancing academic, business, and social responsibilities. That being said, getting more than six hours of sleep is quite the rarity, so perhaps the better answer is that I’ve become better accustomed to a perpetually packed schedule and making the most of my rare downtime.

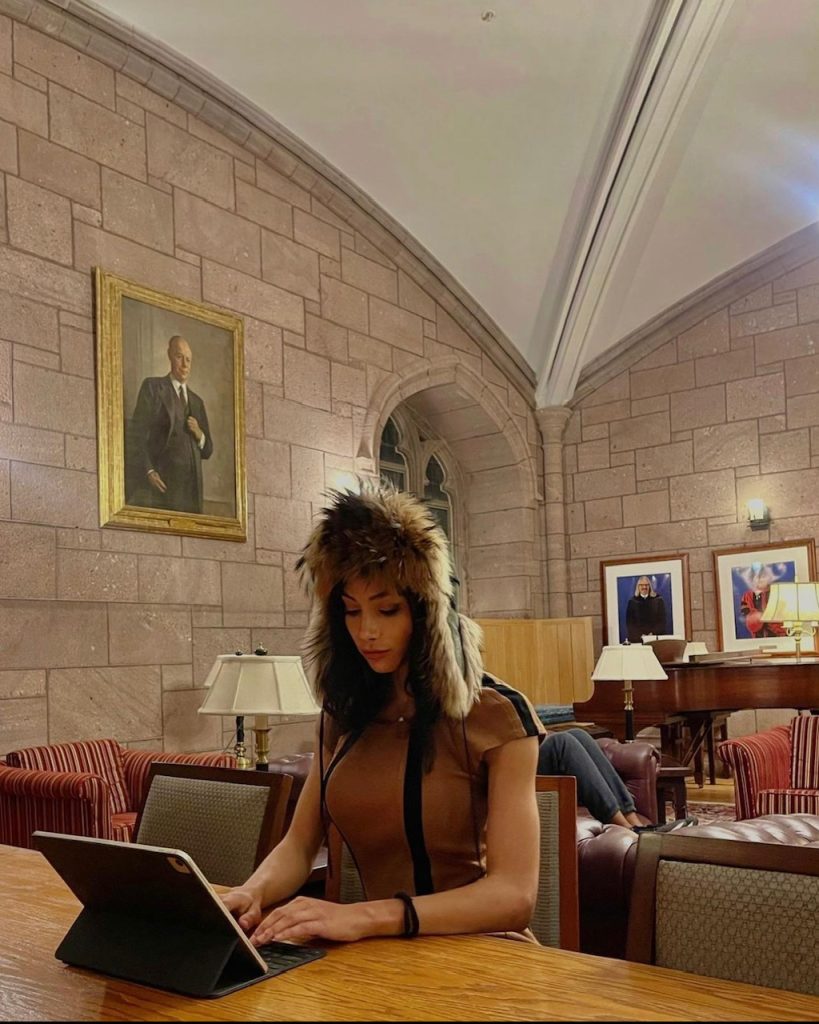

Rakel at work in JE’s lower Taft library. Photo credit: Rakel Tanibajeva JE ’24.5

Any specific interplay between your time at Yale/JE and in the business world?

I’m extremely grateful for the resources and community here at Yale. The Tsai Center for Innovative Thinking at Yale (Tsai CITY) in particular has extended many opportunities to entrepreneurs at Yale, including myself, from educational programs, to funding, to mentorships. I’m still close to my Tsai CITY cohort and our group chat is still active, despite several teams now being scattered across the globe. JE is also where I take many of my business meetings and is the background to many of my business pitch videos. It was during my time at Yale and involvement with Tsai CITY that I founded YouBio. Tsai CITY was a place where I found tangible ways to accelerate the scale and scope of my social and environmental impact and its returns; and from that support, I’ve gained the tools to better my fundraising efforts and expand my team, processes which are still ongoing as I recruit material scientists and fungi biologists, law students with knowledge in IP and patent law, and social media interns.

Rakel Tanibajeva is an environmental studies major at Yale. You can reach her at rakel.tanibajeva@yale.edu

Thank You!

Thank you for reading the Trust’s 2023 newsletter. In ten short years, we’ll be celebrating a century of JE!

If you are interested in obtaining a copy of The Spiders’ Way, a beautifully written and illustrated history of the college, you can find information here.

And you can browse our December collaborative store with Campus Customs here before it closes on December 11th!

We’d like to hear from you! Please consider sharing your thoughts about this project here.

Our best wishes for a happy holiday, from the Jonathan Edwards Trust!

This project would not have been possible without the diligent support of the JE Trust team–Eve Rice JE ’73, JE Trust Chair, Miko McGinty JE ’93 JE Trust Vice Chair, Masu Haque Khan JE ’95, JE Trust Trustee, and Lydia Burleson JE ’21, JE Trust Alumni Engagement Coordinator–and our JE student photographers and collaborators–Kamalu Ogatu JE ’25, JECC President, Emmett Solomon JE ’23+1, JECC Vice President, Rakel Tanibajeva JE ’24.5, Kelly Tran JE ’27 and Matias Guevera JE ’26. Special thank you to former JE Dean Mark Ryan, former JE HOC Penny Laurans, and current JE HOC Paul North for contributing splendid content celebrating JE’s 90 years, and to our wonderful editor for this project Barney Latimer JE ’93.